Outline of a mathematical theory of computation

- 9 minsReference: Dana Scott: Outline of a mathematical theory of computation. Oxford University Computing Laboratory, Programming Research Group 1970: 169-176. paper

This paper (available at paper) introduces a mathematical, rather than operational, theory of computation. The theory explores the idea that we can partially order data types by a relation, and can consider them as complete lattices. The author shows the properties of these lattices and functions over such data types.

In this paper and the related works, Scott initiated the study of “domain theory”: he formalized a notion of “incomplete” or “partial” information to represent computations that have not yet returned a result. The domain of computation has an ordering relation, which represents a hierarchy of information or knowledge (information orderings). The higher an element is within the order, the more specific it is and contains more information. The domain theory models computation by applying monotone functions repeatedly on elements of the domain to refine a result; the calculation finishes when reaching the fixed point. (ref: wiki)

The mathematical meaning of a procedure is the function from elements of the data type of the input variables to elements of the data type of the output, independent of the means of computation. In contrast, the operational meaning provides the trace of the history of the computation, an explicitly generated, step-by-step, evolved sequences of operations on representations. Since the program still runs on a machine, we would like the mathematical semantics to lead to an operational simulation of the abstract entities.

For a function, we can know whether it is computable without knowing how to compute it, similar to that we know an infinite series is convergent without knowing its sum. An adequate theory of computation should provide the abstractions (what is computable) as well as their physical realization (how to compute them).

Problem of self-application

A store is a mapping (function) that connects contents to locations. The current state of the store is

\[\sigma: L \rightarrow V\]which assigns each location \(l \in L\) the content \(\sigma(l) \in V\). A side effect is a change of the state. A command is a request for a side effect. Let S be the set of all states, a command is a function that transforms old states into new states.

\[\gamma: S \rightarrow S\]We also store commands. Let \(l\) be a location at which the command is stored, then \(\sigma(l)\) is a command. Thus we have the following equation.

\[\sigma(l): S \rightarrow S\]Therefore, \(\sigma(l)(\sigma)\) is well-defined. Or is it? Operationally, we store the command as “text” rather than function, but the formal description of how it works remains unclear.

Data types and mappings

Data types are different from data structures. Suppose \(x, y \in D\) are two elements of the data type \(D\), then instead of thinking of them as being separate entities because they may be different, we consider that x, y may approximate the same entity. If y (possibly) contains more information than x, we denote as below.

\[x \sqsubseteq y\]A data type should always provide \(\sqsubseteq\), which is reflexive, transitive, and antisymmetric.

Axiom 1. A data type is a partially ordered set.

Let D and D’ be two data types, with partial orderings \(\sqsubseteq, \sqsubseteq'\) respectively. Suppose \(f: D \rightarrow D'\) is a mapping of the elements of D into D’.

\[x, y \in D, x \sqsubseteq y \text{ implies } f(x) \sqsubseteq' f(y)\]Axiom 2. Mappings between data types are monotonic.

Completeness and continuitiy

An infinite sequence of approximations is of the following form

\[x_0 \sqsubseteq x_1 \sqsubseteq \ldots \sqsubseteq x_n \sqsubseteq x_{n+1} \ldots\]The author assumes that \(x_n\) are tending to a limit, which is the least upper bound (l.u.b). Let the limit be y, we have

\[y = \bigsqcup_{n=0} ^ {\infty} x_n\]If we consider successive terms as giving us more information, then the limit represents a “union” or “join” of the separate contributions. The author assumes that every subset of the data type has a least upper bound. Moreover, the existence of arbitrary least upper bounds implies the existence of greatest lower bounds (g.l.b). Therefore, we have a complete lattice.

Axiom 3. A data type is a complete lattice under its partial ordering.

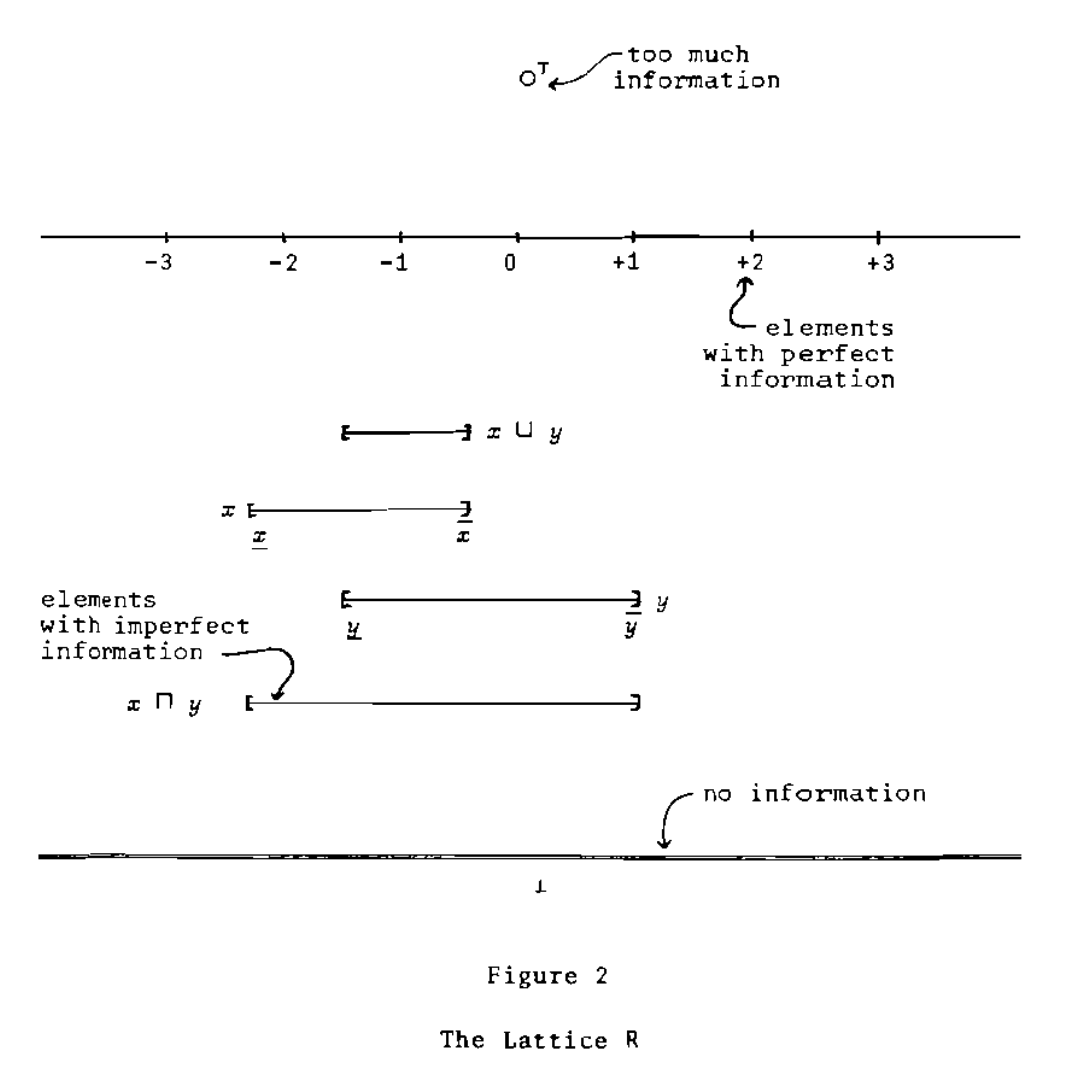

For \(x, y \in D\), they may not approximate the same entity. In this case, x and y are inconsistent. We still assume that they have a l.u.b, \(x \sqcup y \in D\). Even worse, we assume the whole of D has a l.u.b, which denote as “top” of the lattice, \(\top \in D\), the largest element. It is not a “perfect” element, but rather an “over-determined” element. If x and y are inconsistent, then their l.u.b is the top element.

\[x \sqcup y = \top\]The l.u.b of the empty subset of data type is the “bottom” of the lattice, the “smallest” element in the partial ordering, the most “under-determined” element. The least upper bound of the set of all lower bounds of a subset \(X \subseteq D\) is the greatest lower bound \(\sqcap x \in D\). If there is no overlap of information between x and y, we say they are unconnected, and denote it below.

\[x \sqcap y = \bot\]The author uses directed sets to express the notion of limit. A subset \(X \subseteq D\) is directed if every finite subset has an upper bound \(y \in X\)

\[x_0 \sqcup x_1 \ldots \sqcup x_{n-1} \sqcup x_{n} \sqsubseteq y\]A directed set is always non-empty. The limit of the directed set is the l.u.b \(\sqcup X\). Suppose we want a “finite” amount of information about \(\sqcup X\), each “bit” we need is contained in some element of \(X\). By directedness, all of it is contained in at least one element of \(X\). If we consider a monotonic function, the information about \(f(\sqcup X)\) is the “limit” of its “finite” parts.

\[f(\sqcup X) = \sqcup \{ f(x): x \in X \}\]The mapping preserves the limit. A mapping that preserves all limits is continuous.

Axiom 4. Mappings between data types are continuous.

A function of two variables (g(x, x) below) is continuous if it is continuous in each of its variables separately.

\[f(x) = g(x, x)\]The function f is also continuous, but it does not preserve arbitrary l.u.b. Neither should we expect that composition preserves g.l.b: one cannot expect any “smoothness” while decreasing information.

Computability

The author defines computability in terms of topology and recursion theory. Without getting into details (see the reference in paper for formal definitions), the main take away is that an element is computable if we are able to give better and better approximations to x which converge to x in the limit. The data type can have uncountably elements, while there are countably many computable elements. Many sequences can converge to an element x; knowing x is computable does not mean the best way to compute it is known. The computability leads to another axiom.

Axiom 5. A data type has an effectively given basis.

Construction of data types

All finite lattices satisfy the axioms. For infinite structures, the paper presented following examples.

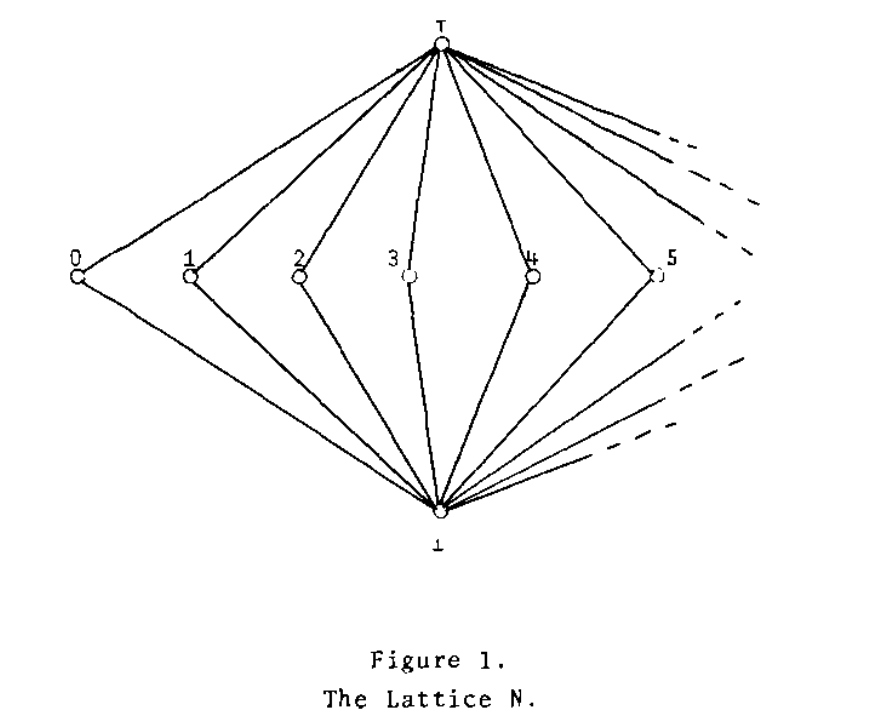

The elements of lattice N are 0, 1, 2, … plus \(\top, \bot\). The whole lattice is its own basis.

The elements of lattice R are closed intervals of ordinary real numbers plus \(\top, \bot\). The basis contains the intervals with rational end points plus the element \(\bot\).

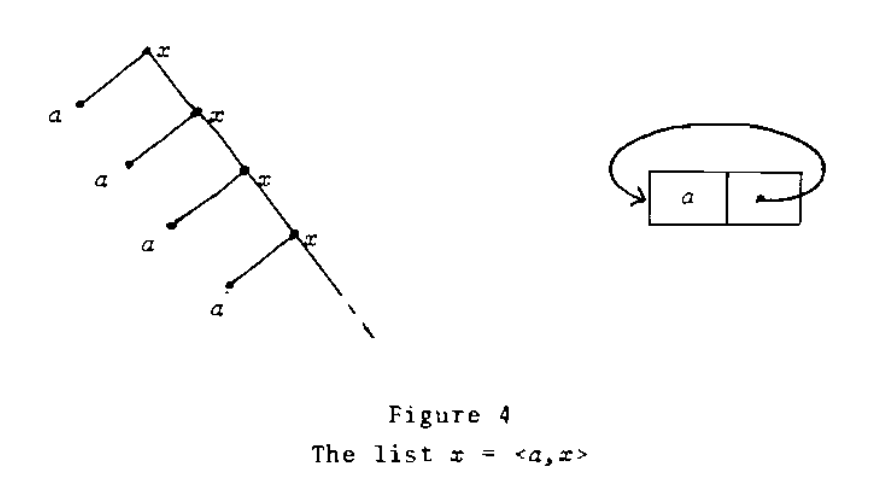

Every continuous function mapping a complete lattice into itself has a fixed point. For a fixed point

\[x = <a, x>, x = <a, <a, <a, \ldots>>>\]

The author also defined a mathematical model for the \(\lambda-calculus\), true “up to isomorphism”, which is also the solution to the self-application problem.

\[D_{\infty} = (D_{\infty} \rightarrow D_{\infty})\]