Generics of a higher kind

- 5 minsReference: Adriaan Moors, Frank Piessens, Martin Odersky: Generics of a higher kind. OOPSLA 2008: 423-438. link

This paper (available at link) describes type construtor polymorphism in Scala. Before this, first-order parametric polymorphism has become mainstream in object-oriented languages, such as Java, under the name of generics. Generics allow programmers to abstract over types using type constructors, but not over type constructors. Authors describe how type construtor polymorphism can reduce code duplications and improve the expressiveness of the language, and detail their design and implementation in Scala.

Scala Basics

- Syntax

- A Scala program is roughly a tree of nested definitions

- If the root of the tree is the compilation unit, the next level consists of objects and classes (keyword object, class, trait), which contain members (classes, objects, a constant value member (val), a mutable value member (var), a method (def), a type member (type))

- A definition starts with a keyword, followed by its name, a classifier, and the entitity to which the name is bound (keyword/name/classifier/bound-entity sequence)

This definition introduces a function len that takes a String and yields an Int by calling String's length method on its argument s. val len: String => Int = s => s.length "val": keyword "len": name "String => Int": classifier "s => s.length": bound-entity

- Function

- Functions are first-class and we can write them directly

x: Int => x + 1 - A method is similar to a function, except that a method is called on a target object. See the example above for function len.

- The internal representation of a function is an object with an apply method

object len { def apply(s: String): Int = s.length }

- Functions are first-class and we can write them directly

- Classes, traits, and objects

- A class can inherit from another class and one or more traits

- A trait is a class that can be composed with other traits using mixin composition

- Type parameters

class List[T]vs type memberstrait List {type T}- Visibility

- A type parameter is syntactically part of the type that it parameterizes

- A type member – like value member – is encapsulated and needs explicit selection

- Scope

- A type parameter is local to its class

- A type member is inherited

- Concrete

- A type parameter is made concrete using type application

List[Int] - A type member is made concrete using abstract type member refinement

List{type T=Int}

- A type parameter is made concrete using type application

- Visibility

- A method defines one or more lists of value parameters in addition to a list of type parameters. A method is a value that abstracts over values and types.

- An object is a class with a singleton instance

Reducing code duplication with type construtor polymorphism

Authors demonstrate the benefit of type constructor polymorphism through several examples. The first example looks at Iterable.

trait Iterable[T]{

def filter(p: T => Boolean): Iterable[T]

def remove(p: T => Boolean): Iterable[T] = filter (x => !p(x))

}

trait List[T] extends Iterable[T]{

// Both methods are redundant!

def filter(p: T => Boolean): List[T]

def remove(p: T => Boolean): List[T] = filter (x => !p(x))

}

With type constructor polymorphism, Iterable now takes two parameters, one for the type of the elements, and the other for the type constructor. Container is a type parameter that takes one type parameter.

trait Iterable[T, Container[X]]{

def filter(p: T => Boolean): Container[T]

def remove(p: T => Boolean): Container[T] = filter (x => !p(x))

}

trait List[T] extends Iterable[T, List]

Another example is comprehensions, which provide a simple mechanism for dealing with collections by transforming their elements (map), retrieving a sub-collection (filter), and collecting elements from a collection of collections in a single collection (flatMap).

Each of these methods interprets a user-supplied function in a different way to derive a new collection. The only collection-specific operations required by a method are iterating over a collection (Iterator abstraction) and producing a new one (Builder abstraction).

trait Builder[Container[X], T] { // <- type constructor polymorphism!

def +=(el: T): Unit

def finalise(): Container[T]

}

trait Iterator[T] {

def next(): T

def hasNext: Boolean

def foreach(op: T=> Unit): Unit = while (hasNext) op(next())

}

Types and kinds

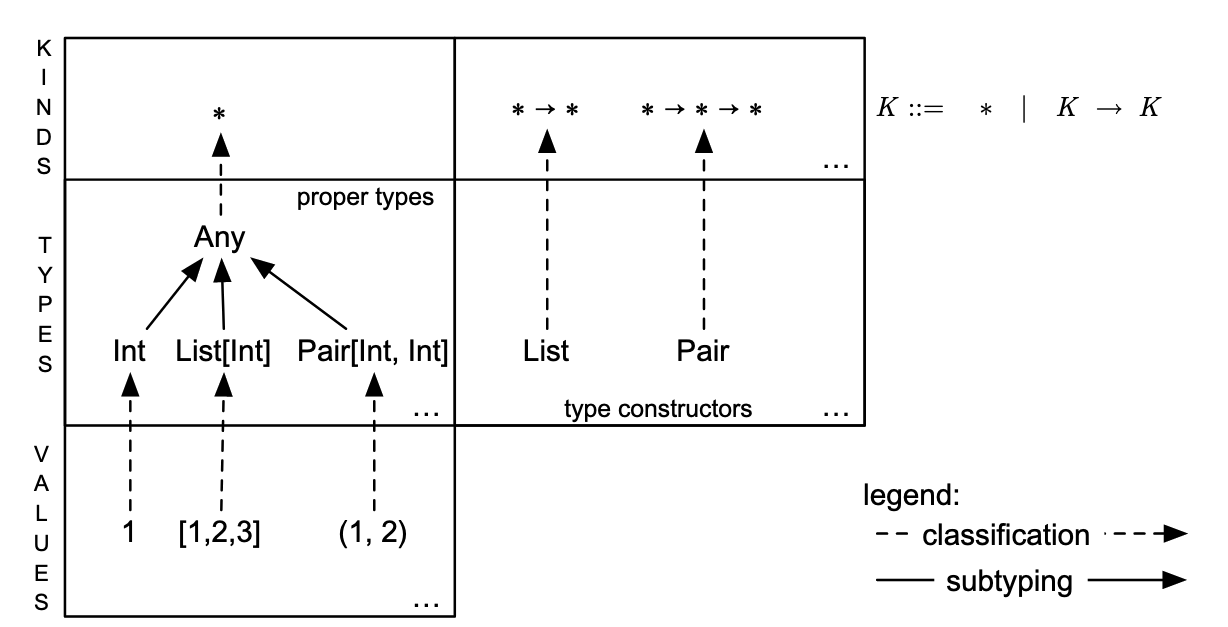

Kinds are used to distinguish a type parameter which is a proper type, such as List[Int], Int, from a type paramter that abstracts over a type constructor, such as List. kinds classify types, and types classify values. Kind constructor constructs kinds.

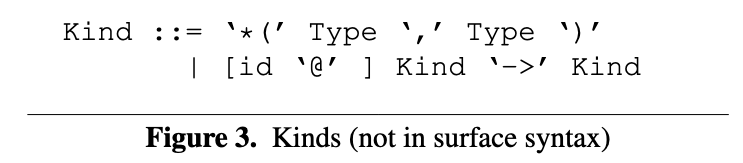

Kinds are inferred by the compiler. Scala’s surface syntax does not include kinds. *(T, U), classifies proper types and tracks their lower (T) and upper (U) bounds. Since type declarations either explicitly specify bounds or receive minimal lower bound (Nothing) and maximal upper bound (Any), the first kind is easy to infer. We abbreviate *(Nothing, Any) to * and *(Nothing, T) to *(T).

Container[X] introduces a type constructor parameter of kind * -> *

Authors refine the kind of type constructors by turning it into a dependent function kind. The syntax for higher-order type parameters provides all necessary information to infer a dependent function kind for type constructor declarations.

Container[X] <: Iterable[X] implies the kind X @ * -> *(Iterable[X]) for Container

Subkinding relates kinds, similar to how subtypes relate types. Subkinding follows rules we defined for type member conformance: *(T, U) <: *(T', U') if T' <: T and U <: U'.

Implementation

Type constructor polymorphism introduces an indirection through the kinding rules in the typing rule for type application, so that it uniformly applies to generic classes, type constructor paramters, and abstract type constructor members. For implementations, extending Scala compiler boils down to introducing another level of indirection in the well-formedness checks for types. Thanks to type erasure in the backend, authors only need to change the type checker.